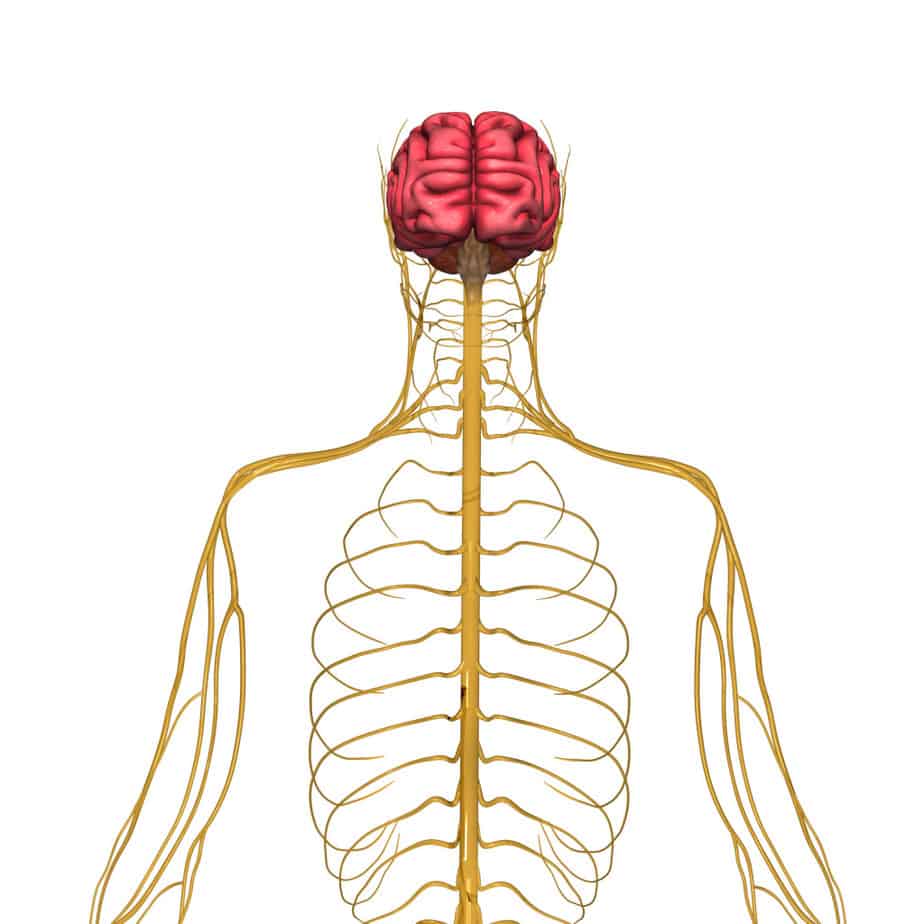

The autonomic nervous system is that part of the nervous system that is responsible for homeostasis and the flight-or-fight response. Generally, the autonomic system operates without conscious input. It is triggered by our emotional response, as well as complex hormonal feedback loops. This autonomic nervous system is composed of the sympathetic and the parasympathetic systems. You can think of the sympathetic system or adrenergic system like depressing the gas pedal in a car, whereas the parasympathetic or cholinergic system is more like taking your foot off the gas.

The sympathetic system is activated in times of stress: elevated heart rate and blood pressure, dilated pupils, and shunting blood away from extremities toward core organs, making skin cool and pale. Think of how you feel when you are frightened or under stress.

The parasympathetic system is the “rest and digest system.” So when you are feeling calm the heart rate is lower, blood pressure is lower, pupils not dilated, skin warm and red. Both of these systems can be and often are affected by medications or street drugs. Some drugs affect the adrenergic (sympathetic) and others affect the cholinergic (parasympathetic). Knowing the pharmacology of common drugs gives clues both in the diagnosis of drug side effects or overdose as well as the antidote.

The following case illustrates this: Many years ago I was working in a rural area. I got a call from the jail at midnight. They had three teens there that were arrested after breaking into a pharmacy. The report was that two of the boys were trying to catch birds in the jail cell and the third looked like he might be building a nest. They had been found with an empty bottle of Dimenhydrinate (antihistamine used for nausea). They apparently were fairly naïve about drugs, when you consider they could have found better medicines to get high with – after all, they had access to the entire pharmacy!

When they arrived in the ER, two of the patients actually looked fairly normal and were no longer hallucinating. However, the third patient was actively hallucinating, confused, agitated, and combative. Airway was open, breathing unlabored, and O2 sat on room air normal. Heart rate was elevated, blood pressure low, skin dry, pink, and warm, and pupils dilated. An IV was placed and fluid support started, and he was given a very small dose of physostigmine IV (cholinergic agonist) by slow IV push.

Immediately his sensorium cleared and he was able to communicate coherently. Afterward he was placed in the ICU for the night for observation, cardiac monitoring and further fluids.

The following morning, about eight hours later, I got a call by a concerned nurse that the boy was “acting strangely again.” I thought this very odd as the Dimenhydrinate effect should be completely gone by six hours.

When I arrived in the ICU, the patient was restless on his bed. Looking up, I saw two empty IV bags. I asked the nurse if he had urinated. She replied no, two of them had helped him to the commode earlier but he didn’t do anything. I asked if they had stayed in the bathroom with him. They had.

I suspected increased sympathetic tone and decreased parasympathetic tone to the bladder due to acute emotional embarrassment. I got him out of the bed and put him in the restroom by himself. He came out no longer restless and much relieved.