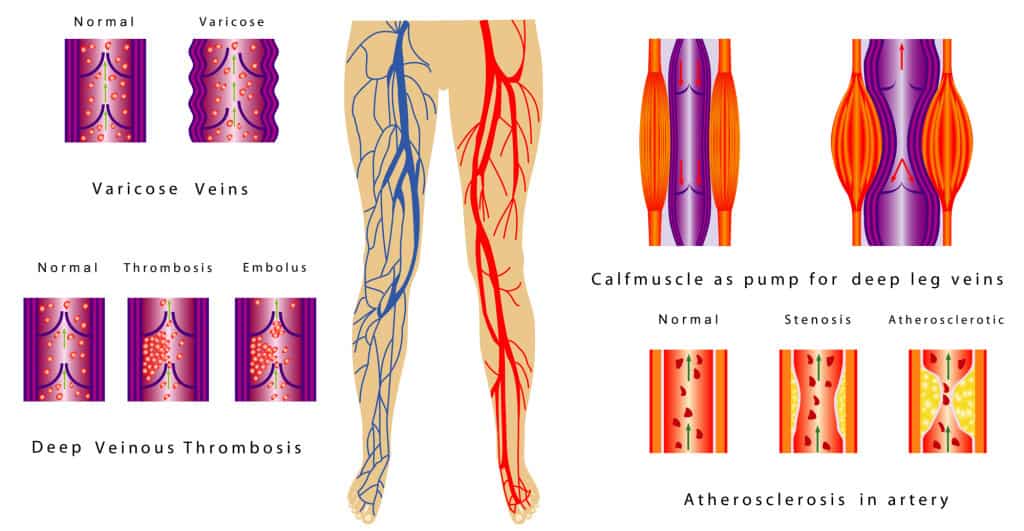

Deep Vein Thrombophlebitis, or DVT as it is usually referred to, is a common condition. Because of this, it is something that should be considered in any patient with an extremity complaint of pain or swelling, or in a patient with chest symptoms. The most common site is the deep venous system of the lower extremities. It may present as mild or moderate pain, unilateral edema is usually present, there will usually be tenderness to palpation over the posterior midline of the calf, other signs of inflammation such as redness and heat are often absent because the deep veins are under the muscles.

When blood clots in a deep vein there is a risk that some of the clot will break off. This is known as an embolus. If this happens, many emboli will often travel within the venous system to the heart and then on to the lungs. In the lung, they will lodge in and block arterial blood flow in branches of the pulmonary artery. This will result in inflammation and death of lung tissue supplied by those vessels causing pleuritic (pain on inspiration) pain, shortness of breath, and sometimes a cough with bloody sputum.

There are 3 factors that can lead to a DVT: the state of the veins, the coagulability of the blood, and stasis of blood.

In vessels that are damaged, as in the case of trauma, a clot is more likely to develop. Note though, clotting is a normal process to prevent hemorrhage from damaged capillaries. Bruises and hematomas should not be mistaken for DVTs. A DVT is a clot formed within a deep vein whereas bruises and hematomas are the result of blood seeping into the tissues out of the vascular system and pose no risk of embolism, even though they are particularly concerning to patients and their families.

The coagulability of blood is dependent on a complex enzymatic cascade of clotting factors. There is always a balance between clotting too easily, resulting in a DVT, and too slowly that results in unnecessary bleeding. This delicate balance of reactions is dependent on both our genetic makeup as well as environmental influences such as drugs like the BCPs or nicotine which tips the balance toward clotting and chronic disease such as cancer.

The third and final consideration is stasis: blood that is not moving is more likely to clot. The flow of blood in the venous system of our legs is dependent on muscular activity. When you walk, your calves are actually helping to pump venous blood back to the heart.

Knowing the 3 factors that can lead to the formation of a clot, you can look for clues in the history that will raise your suspicion: was there an injury to an extremity? Is there a family history or past history of DVT? Does the patient smoke? Does the patient take hormones such as BCPs? Has there been a long period of confinement such as an illness that kept the patient in bed or has the patient been on a long trip recently?

By the time you are called for a patient with a DVT, they often have symptoms of a pulmonary embolism (PE) already. Usually chest pain or shortness of breath is the reason for the call. Always be sure to ask about leg symptoms in any patient with chest symptoms. Patients may not think it important to mention. And remember to give oxygen early as you start your assessment.